Read an Excerpt from Touch and Go by Studs Terkel

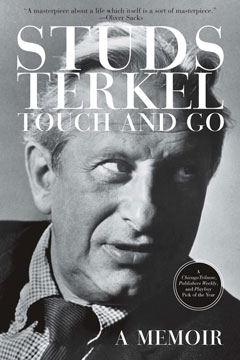

This week, we're celebrating Stud’s Terkel’s birthday with a series of posts honoring his legacy. Today, we are sharing an excerpt from his final memoir, Touch and Go, published just two years prior to his death. Studs Terkel dedicated his life to telling people’s stories on his radio show and in his books, so it comes as no surprise that much of his own story is told through and around the stories of the people he met. In this chapter from Touch and Go (edited for length), Terkel reflects on the Great Depression and the people who strove to make a difference during a difficult time.

* * * * *

If ever there was an experience that altered my life, not simply in a political way, but in every aspect, it was the Great American Depression. I was there watching what hard times did to decent people. The great discovery is how they behaved during a specific issue, not what they were labeled. It was easy to call somebody a Commie, or a Red, or a Fascist for that matter. It’s how that person behaved at a certain moment that counted.

I remember the generosity practiced by those with little. A guy would leave to get on the streetcar and he’d pass another guy a cigarette, or, getting off, would hand someone else his transfer. There were these little things. There’s the innate decency of human beings. But when your livelihood is at stake, it’s you or the other guy, not you and the other guy.

…

I shall never forget an assemblage known as the Workers’ Alliance, sometimes called the Unemployed Council. Always labeled as Commies and Reds. These groups were in certain of the big cities, among them Chicago and New York.

The bailiffs were very busy evicting people, sometimes three or so families a day. For the most part, the bailiffs weren’t bad guys and hated their work dispossessing others. They’d arrive during the day to take the furniture out of the homes of people being evicted—removing bedsteads and kitchen tables and even the toilet seats, everything but the kitchen sink. They’d take out the furniture and shut off the electricity and the plumbing. This happened more often in the deeply poverty-stricken neighborhoods, but I read of it in the papers every day.

When the bailiffs were done evicting people, the sidewalks would be full of furniture and clothes and pots and pans. At the end of the day, as soon as the bailiffs quit, a group of guys would come along.

It is true that the Communist Party formed the basis of the Workers’ Alliance. They were full of unemployed craftsmen; among them were electricians, carpenters, plumbers, and gas men. They would put the furniture back in and restore all of the utilities. They’d keep doing that until the bailiffs finally got tired, and in many cases, the bailiffs got so tired, they quit.

That was how some of the people acted at that time. If one tried to be doctrinaire and impose his Communist philosophy on another, that was something else. You weren’t needed. Out. No other matters counted at that moment but that the people needing help were helped.

Hundreds of miles away, in Montgomery, Alabama, Virginia Durr suffered a similar discovery as a member of an organization known as the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. This relatively small group was composed of people fighting segregation, most of them white.

Civil rights activists were always accused by certain forces of being Communist. During the 1940s, there was a witch hunt, and Virginia was called to testify as an unfriendly witness before the Eastland Committee. Senator Jim Eastland, an avowed racist and the boss of Sunflower County, Mississippi, had set up his own Un-American Activities Committee.

I remember seeing Durr’s name, and a picture, in the newspapers: The headline: Southern Rebel Defies Eastland. Picture Eastland, all three hundred furious pounds of him: “Are you or have you ever been . . .” In the wonderful photograph, Virginia sits in what is obviously a witness chair, legs crossed, powdering her nose. She will not satisfy her interrogator with a response. Senator Eastland is going crazy and finally orders her off the stand. The reporters surround her; they’re entertained by her actions. One asks, “What impelled you to defy this powerful man?”

She says, “Oh, I think that man is as common as pig tracks.” Then she sighs, “Oh, I guess I’m just an old-fashioned Southern snob.” That’s the way she talked, and oh, she was a powerful presence.

She made it clear to the senator that it didn’t matter what a person was labeled; all that mattered was what that person did under specific circumstances. In this case, the battle of the Southern liberals was to eliminate the poll tax that deprived so many African Americans of the right to vote. Among the members of her little group might have been one or two Reds. But that’s not what mattered to Virginia. How did a person behave on the issue of the poll tax? It was analogous to the work of the Unemployed Council.

…

Virgina wrote a book called Outside the Magic Circle. In the preface, I described the three ways she could have lived her life. She was the daughter of a preacher who lost his faith: He couldn’t believe that Jonah set up light housekeeping in the belly of the whale. I said that since she was part of a white, upper-middle-class society, she could have led an easy life, been a member of a garden or book club, and behaved kindly toward the colored help. Two, if she had imagination and was stuck in this nice, easy world, she could go crazy, as did her schoolmate Zelda Sayre, later the wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The third is the one she took: She became the rebel girl and basically said, “The whole system is lousy and I’m going to fight it.” That’s stepping outside the magic circle.

The Durrs were highly respected citizens of Montgomery until the fight to break segregation. They were friends of Myles Horton, who established Highlander Folk School, the first integrated school in the South since the Reconstruction, in Monteagle, Tennessee. It was primarily a school for adults who were organizers of labor and civil rights—white and black together. Myles was a Southerner who had studied theology at Vanderbilt and was brilliant as a teacher of adults. One of his influences was Paolo Freire, a great Brazilian educator who revolutionized the use of language. Certain words are key, words that arouse emotions because they resonate with peoples’ lives: Hunger. Cold. Equality. Justice.

Highlander was burned down by the Klan, but it was reestablished in New Market, Tennessee, where it still exists. Martin Luther King Jr. went to Highlander. I was at Highlander once, very briefly. Pete Seeger went there a lot. Rosa Parks went there, too. For a time, she was the seamstress for Virginia Durr, and she often talked with her about the battle for equality. Virginia is the one who urged Rosa Parks to attend Highlander, after which she became secretary to E.D. Nixon, a former Pullman car porter who became the head of the NAACP in Montgomery.

All this played a role when Rosa Parks sat down and refused to get up on that bus. It was Virginia Durr who bailed Rosa Parks out of jail. It was Clifford Durr who represented Rosa Parks in Federal court after the Montgomery Bus Boycott—arguing that the Montgomery ordinance segregating passengers on city buses was unconstitutional.

The night the Selma-to-Montgomery march ended at George Wallace’s mansion, he was furious. Wallace underwent a change after he was shot, but back then he appeared on TV naming the subversives responsible for all the troubles. Half of them were sitting in the Durr living room watching the news. History has shown these people to have been visionaries; they’ve been referred to as the prescient or prophetic minority. Virginia Durr fit that description especially well.

* * * * *

Want more Studs Terkel? Pick up a copy of Touch and Go, or check out our reading list to learn more about his other works.