Read an excerpt from Mouths of Rain

By:

DerekThursday, June 10, 2021

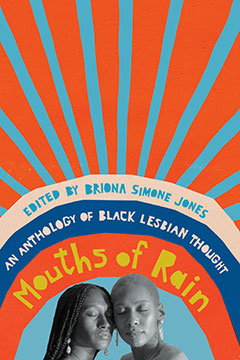

African American lesbian writers and theorists have made extraordinary contributions to feminist theory, activism, and writing. Earlier this year we published Mouths of Rain: An Anthology of Black Lesbian Thought edited by Briona Simone Jones, a groundbreaking collection that traces the history of intellectual thought by Black Lesbian writers. Mouths of Rain features poems, songs, essays, and speeches by luminaries like Audre Lorde, Cheryl Clarke, Dionne Brand, Kai Davis, Barbara Smith, Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, and others.

To celebrate Pride Month, we're sharing an excerpt from Mouths of Rain by writer and scholar Alexis Pauline Gumbs. Her essay "Mouths of Rain: Be Opened" examines the power of ancestral connections and the way stories can nourish future generations.

* * * * *

In Anguilla they say that my grandmother knew how to control the rain. No one ever told me that she had those powers while she was alive, but on the way to her funeral the rain stopped just in time for us to get out of the cars and walk into one of the several local churches where my grandmother Lydia organized. That’s when my Aunt Una said it: “That’s mommy telling us she’s with us; you know, everyone said she could control the rain.”I would have loved to ask my grandmother whether she was Storm from the X-Men. But all I have are archival materials that I piece together as a kind of evidence. Yes. My grandmother was the founder of the Anguilla Beautification Society, a group of people committed to growing flowers on a desert island. Yes. My grandfather, who often lived apart from my grandmother, would write letters asking her to send rain. And sometimes he included graphs of the local water table, so it seems he meant it quite literally. When it was time to go through my grandmother’s jewelry and divide it among granddaughters, the necklace that spoke to me was a large turquoise stone, evidence of gathered elements, used in Navajo culture to invite rain. I now wear it almost every day. All that is to say, I can say yes.My grandmother had a special relationship to rain. Or maybe her water power was a community-held metaphor. My grandmother had that kind of impact, like water in the desert. She nourished the communities where she was planted. She founded hospitals and service organizations; she was involved in all the churches because that was where the people were organized. She even designed the flag during the Anguillian Revolution in 1967. Three dolphins swimming in a circle. Like water nourishing the ground, she made the impossible bloom. And in the years after my grandmother’s death, Anguilla has become so lush and green, you would almost never know it had ever been a desert island. So yes. I have my own reasons to believe in the power of rain.It was on that same island, Anguilla, vacationing with the scholar and activist Gloria Joseph, that poet, theorist, and icon Audre Lorde began to imagine a new form of fertility for herself. According to biographer Alexis De Veaux (an icon in her own right, also featured in this book), Lorde’s experience in Anguilla inspired her to make a decision that would add years to her life—to move full-time to the Caribbean. Lorde had imagined the Caribbean as a mythical ancestral home because her parents were from Grenada and Barbados, but her time collaborating with the Women’s Coalition in St. Croix and visiting Anguilla helped her decide that living in the Caribbean was practical for her physical health and peace of mind. The decision to live in the Caribbean was also a decision to make roots with another Black woman, Gloria Joseph, another form of homecoming that watered the last years of her life.Now Anguilla calls herself “rainbow city” and the tourist board markets the country as an island of rainbows. I am almost 100 percent sure that no one on the Anguillian tourist board was inspired by the rainbow symbols of the gay pride flag. Rainbows, which one can see frequently in Anguilla, come from the fact that Anguilla has become a place with short rain showers followed by sun, the wind-propelled variance resulting in prismatic reflection; sunshowers lead to rainbows. Of course, as Audre Lorde would learn in 1989 in St. Croix, too much rain and wind in the Caribbean, the ferocity of the still outraged winds of the transatlantic slave trade routes, can result in devastating hurricanes, and now because of climate change more frequently they do. In 2017, Anguilla experienced the most destructive hurricane in local history.Oya, the Yoruba goddess of the storm, of change, is also the keeper of the graveyard, the ancestral connector, the helix. Audre Lorde learned from a priest late in her life that she was a daughter of Oya. The hurricane is also represented in Orisha iconography by the rainbow. Was my grandmother a representative of Oya? Family lore suggests she was definitely in touch with her rage, and she was undoubtedly a change maker in her community.What does it mean for us, readers, writers in what Briona Simone Jones calls and claims as an expansive Black lesbian literary tradition, to claim an intimate relationship with rain at a time of climate change and wildfires, in a time thirsty for ancestral remembrance and change? Is there a relationship to the legacy of this tradition of women nourishing each other and ourselves, often in spaces that seem hostile to the growth of our love and the healing change our planet needs right now? And is it possible?

* * * * *

For more about Mouths of Rain and other LGBTQ titles, check out our Pride Month Reading List.

Blog section: