Still Doing Life Open Exhibit

By:

DerekFriday, August 12, 2022

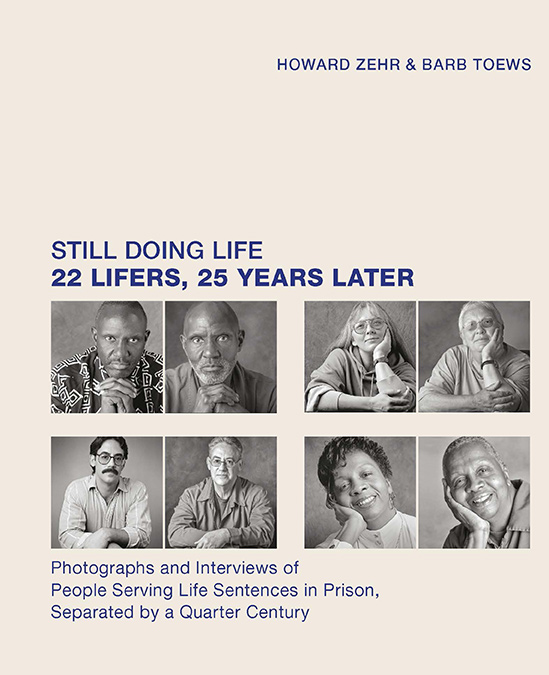

In 1996, restorative justice advocate, photographer, and bestselling author Howard Zehr published Doing Life, a book of photo portraits of individuals serving life sentences without the possibility of parole in Pennsylvania prisons. Twenty-five years later, Zehr and Barb Toews, an associate professor of criminal justice at University of Washington, Tacoma, co-authored Still Doing Life: 22 Lifers, 25 Years Later, where many of the same individuals are revisited, interviewed, and photographed in the same poses. In the new book, the portraits are featured side by side, creating a visceral story of how the U.S. justice system, built upon punishment, racial criminality, and bleak possibilities for redemption, fails to break or heal the enduring humanity of lifers or those serving “a death sentence without an execution date,” as Aaron Fox, one of the lifers, notes.

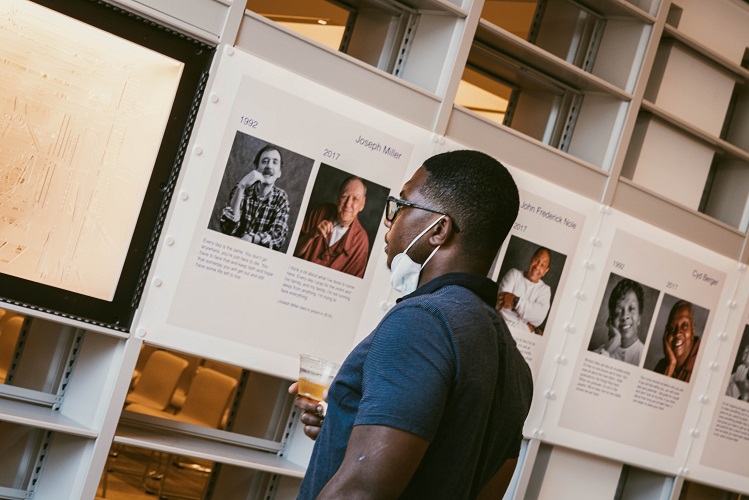

Through a generous grant from the Art for Justice Fund, Still Doing Life has inspired a public exhibit currently at The Free Library of Philadelphia, co-facilitated by Vox Populi Gallery and The New Press, with programming support from Mural Arts Philadelphia. The public is invited to witness the incarcerated individuals’ side-by-side portraits, taken a quarter of a century apart, and to reflect on the interviews. Their hope, regret, and persevering desire to mentor, learn, and grow are contextualized by Zehr and Toews’s restorative justice theory, challenging readers to revise how we respond to fatal harm in a way that does not beget more harm.

Still Doing Life: 22 Lifers, 25 Years Later exhibit at The Free Library. Image by SayTen Studios

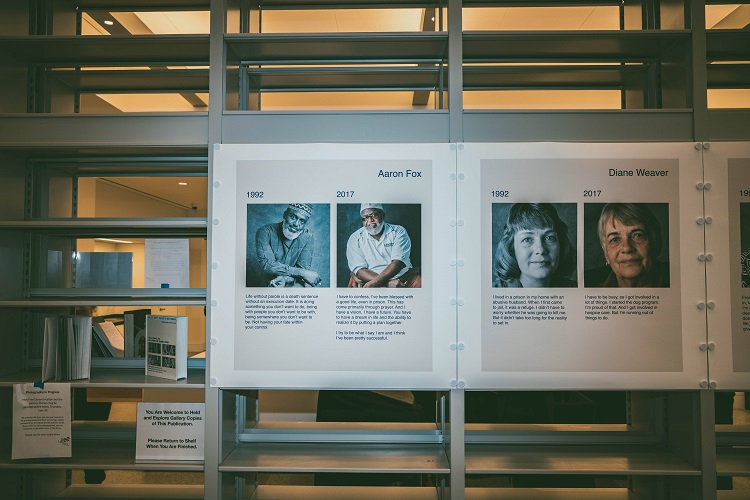

Aaron Fox and Diane Weaver. Image by SayTen Studios

Diane Weaver

Early 1990s: “The longer you are in here, the less ties you have to the outside world. Your family begins to die off. And your friends—how long can someone really stand behind you? They eventually go back to their own lives. That’s sad. That really hurts. It’s also been my choice to decrease visits. They’re hard for me . . .

“Most of the women who work on the prison farm have a certain cow that they take as a pet, name and spoil it, take it apples. I always have one, and my cow just gave birth. I’m a grandma! I’m just tickled pink.”

2017: “It’s forty years that I’ve been in. I’m sixty-seven. This place has changed for the worse over the years. They shut the farm down, so I had to get rid of my bouncing baby bull. There are close to two thousand inmates now, up from around two hundred inmates when I first came here. They put a fence up. The staff are sometimes no better than the inmates . . .

“I gave up my single cell to live with and take care of two residents until they died. They would have ended up living down in the infirmary, and that is no life for people. They both died in my arms. It was hard but also a blessing. I’ve lost all my family since I’ve been here. My father was the last one, and I wasn’t there to take care of him.”

Hugh Williams and others featured in the Still Doing Life exhibit. Image by SayTen Studios

Hugh Williams

Early 1990s: “The worst thing about a life sentence is being stripped of any hope. We all have our own hopes within ourselves, but I’m saying what society will grant. If a person is laid off work, he can get unemployment and food stamps. There are mechanisms to keep people from falling through the cracks, a backup system in society. But in this system, there is no backup. You are just thrown in the penitentiary and told to do it until the Creator calls you back.”

2017: “With the amount of time that I have in, I’ve been a mentor. I’ve raised sons, some little brothers, and a grandson here and there. I try to be as helpful as I can and look out for the young guys. It’s a chore because they got the bodies of men but the mentality of children. I don’t know where they come from, but that’s how it is."

Bruce Bainbridge

Early 1990s: “A life sentence is a tunnel without light at the end. It just goes nowhere. It’s an endless black hole that keeps sucking everything in. That’s all this place does: sucks you in and keeps you here.

“What makes it tolerable is hope. That comes, I guess, from within, from the people around you, from the friends you develop while you’re in here. You can’t exist without hope.”

2017: “When we had to get rid of the civilian clothes due to a policy change in 1995, it was depressing for me because I had to throw away my identity. That’s one of the biggest things that gave me character. I didn’t want to turn into a prisoner. I still struggle with keeping my humanity. I don’t want to get numb to that.”

After the book’s release, authors Howard Zehr and Barb Toews were interviewed by Suzanne Estrella, Pennsylvania Commonwealth Victim Advocate, about the power of Still Doing Life. Their conversation revolved around the need for individuals to be allowed a position where they can view the harm they’ve caused and make something meaningful and restorative from it. Toews emphasized that the power of the project lies in the power of story and the human face to reduce the social distance between people who survive violence and those imprisoned. She notes that the “stories, experiences, and faces” of people serving life sentences without parole can impact people and change their minds about our system of punishment. The project is as much about humanizing the lifers as it is about building survivors’ resilience and capacity for restorative practice.

Both the book and the exhibit ask us to question the morality of a life sentence and the larger criminal justice system from which it extends. They ask us to regard incarcerated individuals with candor and interrogate our own impulses to do away with human beings, who like us, are both capable of harm and worthy of redemption.

Still Doing Life is on view at the Free Library in Philadelphia through August 15, after which the exhibit is scheduled to travel to different cities.

Image by SayTen Studios

Image by SayTen Studios

* * *

This post was written by Mosiah Williams, a summer 2022 New Press intern.