After a long year of waiting, the 2020 Tokyo Olympics Games are here! Many changes have been made this year given the state of the world: there are mandatory daily COVID tests for athletes and a ban on spectators at the stadiums to prevent outbreaks. Despite these changes, protests and controversies in this global arena have remained constant.

World-class athletes and ordinary citizens alike have used the Olympics as an opportunity to make issues of racial inequity and gender discrimination visible on a global scale, and this year is no exception. Various women's soccer teams, from the U.S. to Chile, have exercised their new right to "express their views" on the field by taking a knee before a game, showing their alliance with the Black Lives Matter movement. The women on the German gymnastics team took a stand against the sexualization of their sport by wearing full-body unitards. There was even great controversy about hosting the Olympics in Tokyo; 83 percent of voters said that the games should have been postponed or canceled altogether.

Similar social justice debates arise every four years at the Olympics, and sports journalist and New Press author Dave Zirin keeps a watchful eye on these occurrences. In his book

Game Over: How Politics Has Turned the Sports World Upside Down, Zirin reflects on the political and social impact of the modern sports industry. He explores everything from the devious side of the NCAA to the NFL lockout, showing that sports reflect and shape society.

Below are a few protests and controversies in Olympics history that Zirin highlights in the book.

* * * * * * * * * *

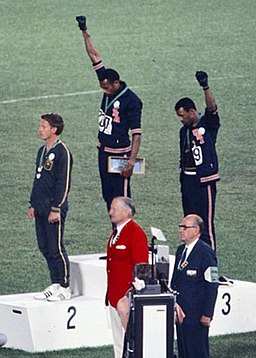

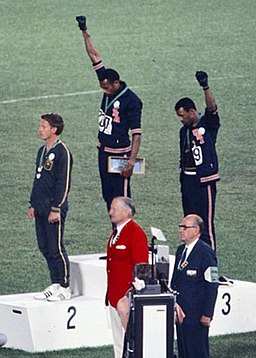

1968 Olympics Black Power Salute

Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gold and bronze medalists in the 200-meter race, used their victory as a moment of protest. They wore beads and scarves in remembrance of lynching victims and they wore black socks with no shoes to highlight racial disparities in income and poverty. But their most iconic form of protest was when they raised their fists to show Black unity and to call for active forms of protest. The Black Power salute was being used as “a cry for freedom and for human rights,” said Smith in a 2008 interview with the Smithsonian.

At the U.S. Olympic Track and Field trial this past June, hammer thrower Gwen Berry mirrored the Black Power salute when she was introduced, showing that the fight for Black liberation is still prominent in the Olympic stage. After being awarded with a bronze medal for the hammer throw in Eugene, Oregon, Berry turned her back on the flag as The Star-Spangled Banner played as an act of protest against systemic racism.

2012 Olympics, Gabby Douglas Attacked for Her Hair

At the 2012 London Olympics, Gabby Douglas made history as the first Black gymnast to win a gold medal in the individual all-around event. She also won gold in the team event with the “Fierce Five,” making them the first American team since 1996 to win. Even though Douglas was beyond successful that summer, online trolls took to Twitter to comment on her hair rather than on her gold-medal-winning performance. They referred to Douglas’s pulled-back ponytail as “unkempt” and “embarrassing.” The 16-year-old had to endure racist critiques of her hair—critiques which were based on western beauty standards. In response, Douglas stood up for herself saying: “I just made history and people are focused on my hair? It can be bald or short; it doesn't matter about (my) hair.” she said. Gendered and racist criticism Black women face is particularly vicious, as Zirin points out, and that Black male athletes—let alone white and other non-Black athletes, of any gender—are far less likely to be criticized for their hair.

This year, anti-Black hair bias has surfaced again around Soul Caps, a professional swim cap designed specifically for afro-textured hair, which the International Swimming Federation rejected for use at the Tokyo Olympics.

2016 Summer Olympics Rio

In preparation for their games, Brazil infiltrated and displaced countless impoverished communities, called the favelas, to construct stadiums and the Olympic village. Hosting the Olympics was pitched as an opportunity to develop Rio’s infrastructure and generate higher economic growth; however, a majority of the population in Rio did not benefit from this opportunity. Zirin quotes a favela resident, Eduardo Freitas: “It looks like you are in Iraq or Libya. I don’t have any neighbors left. It’s a ghost town.” Also, in investing money in the Olympics, the Rio governor declared a “state of public calamity” as Brazil fell into a deeper recession. The state had run out of money to pay for public security and healthcare. Rio residents took to the streets hours before the opening ceremony of the Olympics to protest the Brazilian government. They demanded that the administration focus on investing in their people before funneling billions into sporting events. (Similar patterns are found in the 2012 London Games and the 2008 Beijing Games.)

2012 and 2016 Olympics Caster Semenya

As a young eighteen-year-old, South African runner Caster Semenya set a world record in the 800-meter sprint at the 2009 African Junior Championships. This success, however, launched a long, ill-conceived and discriminatory process of analyzing Semenya’s gender using biological testing. Even though it is normal for hormone levels to vary from person to person, when it was reported that Semenya, who is a cisgender intersex woman, had testosterone levels about three times higher than the “average” woman, the public and athletic organizations critiqued her femininity and discussed whether she should be allowed to compete in the Olympics. Abusive regulations demanded that Semenya chemically lower her testosterone levels in order to compete, which she adhered to from 2010 to 2015 by taking birth control pills. As a result, she experienced abdominal pain, high fevers, and other symptoms. In the London and Rio Olympics, Semenya won the gold medal but she has been in constant strife with the IAAF. Zirin argues that her story reflects the limited understanding of gender in athletic institutions: “What these officials still don’t understand, or confront, is that gender… is a remarkably fluid social construction. Even our physical sex is far more ambiguous than is often imagined or taught.” In 2020, Semenya announced her plans to challenge the World Athletics’s hormone policies in the European Court of Human Rights. Semenya will not be competing in the Tokyo Olympics, and while some governing bodies, like U.S. Gymnastics have introduced policies that are inclusive of intersex, trans, and nonbinary athletes, other organizations, like World Rugby, have leaned into hormone-based bans.

Check out Dave Zirin’s upcoming book The Kaepernick Effect: Taking a Knee, Changing the World. It will be released in September 2021. The book highlights the impact that NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick has had on police brutality protests by taking a knee during the national anthem, and examines this essential sports-politics dimension of today’s movements for racial justice in America.

This post was written by Carolina Cordon, a Psychology and English double major at Amherst College. Cordon is a Summer 2021 New Press intern.

Images:

-

1968 Olympics Black Power Salute - John Carlos, Tommie Smith, Peter Norman. Attribution: Angelo Cozzi (Mondadori Publishers), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

-

Gabby Douglas 2016 Rio Olympics. Attribution: Agência Brasil Fotografias, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

-

Caster Semenya 2012 London Olympics. Attribution: Tab59 from Düsseldorf, Allemagne, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sources:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-