Happy Birthday Andrea Dworkin! A Timeline of Dworkin's Life and Work

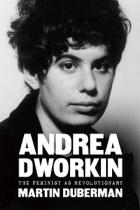

One of the most controversial and iconoclastic feminists of the twentieth century, Andrea Dworkin was born on this day in 1946. Over a decade after her passing in 2005, her work has taken on renewed importance in the wake of #MeToo, raising new questions about how we navigate sex, power, gender, and consent. Earlier this month, The New Press released Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary, an intimate and thoroughly researched biography by leading LGBT scholar Martin Duberman.

Below is a brief timeline of the life and work of Andrea Dworkin- not at all comprehensive, given that she was an incredibly prolific writer and speaker.

September 26, 1945

Andrea is born in Camden, New Jersey, to Harry Dworkin and Sylvia Spiegel, both of whom were of Jewish immigrant backgrounds. Her father, a schoolteacher and a committed socialist, inspired her dedication to justice and equality. Andrea's relationship with with her mother would always be turbulent- she chafed under Sylvia's urging to be "presentable" and marry a "nice " man and have "obedient" children- but later wrote about how her mother believed that both birth control and abortion should be legal, "long before these were respectable beliefs." Though as a teenager, Andrea vehemently rejected all organized religion, the shadows of the Holocaust, of antisemitic persecution faced by her family and by Jewish people throughout history, heavily influenced her later thinking about marginalization and exile; she would later object to Israel's occupation of Palestine and its brutality towards Palestinians.

Andrea was always encouraged by her parents to read and to write; and as a young girl she began writing poetry and fiction. She decided that she would become a writer because, she could "do it in a room alone" and "nobody could stop me."

February 1965

As an eighteen-year-old freshman at Bennington College, Andrea was arrested for participating in a sit-in at the United States Mission to the United Nations, a demonstration she helped organize to protest US escalation in Vietnam. Her brutal treatment at New York's infamous Women's House of Detention created a stir in the media, when she went public with her story.

September 1965

After her ordeal, Andrea did not want to return to normal college life. Determined to see the world outside America, and to become a writer, the 19-year-old Andrea traveled to Europe, eventually settling in Crete. There, she wrote a number of poetry and prose collections, and suffered an abusive relationship with a man, "E." She moved back to America and resumed her studies at Bennington College.

1968

After graduating, Andrea again moved to Europe, this time settling in the Netherlands, where she interviewed the anarchists of the Provo movement during the height of the 1968 uprisings. She also became involved with Cornelius (Iwan) Dirk de Bruin, who would go on to abuse her severely and to stalk her wherever she fled from him. Stranded and in poverty, Andrea turned to sex work and lived wherever she could. It was during this period that she became close with the feminist Ricki Abrams and delved into the radical feminist writing of Kate Millet, Shulamith Firestone, and Robin Morgan. Ricki and Andrea began a book together, which would later become Andrea's groundbreaking text Woman Hating. She vowed at this point to dedicate her life to the feminist movement and the well-being of women.

1972

Andrea returns to New York, where she throws herself into the rapidly growing feminist movement in that city, into anti-war activism and the movement against apartheid in South Africa. She would go on to make a name or herself as an impassioned, inspiring speaker, most notably at the first Take Back the Night march in November 1979 and and her 1983 speech at the Midwest Regional Conference of the National Organization for Changing Men (now the National Organization for Men Against Sexism titled "I Want a Twenty-Four Hour Truce During Which There Is No Rape."

1974

Andrea meets the writer John Stoltenberg when they both walked out of a poetry reading in Greenwich Villiage due to it's misogynistic content. They became fast friends and lived together; though Andrea from that point on identified as lesbian and John as gay, they would consider each other to be their life partners.

Andrea also completes and publishes Woman Hating, which examines how misogyny and male supremacy is deeply rooted in our society and requires female negation; and that this ideology takes on a near-religious significance. It is one of her most well-known books and a seminal text in radical feminist literature.

1980

Linda Borman, who appeared in the infamous pornographic film Deep Throat as Linda Lovelace, publically stated that her husband Chuck Traynor violently phyiscally and sexually abused her and coerced her into making pornographic films. She made these statements at a press conference with Andrea, Catherine MacKinnon, and members of Women Against Pornography. Though Borman decided not to pursue damages against Traynor, Andrea and her comrades would begin work on using civil rights litigation to combat pornography and win damages for women and men who had been harmed by it. Though the ordnances were ultimately unsuccessful, Andrea would continue to advocate for them.

1983

Andrea publishes Right Wing Women, an examination of conservatism and anti-feminism among women, contextualized within the social conservatism of the Reagan era and the New Right.

1986

Andrea testifies before the Attorney General's Commission on Pornography, also known as the "Meese Commission", about the harm caused by pornography to women and men. She denounced the use of obscenity laws, considering them anti-woman and reactionary, but instead urges the commission to consider the matter as an issue of civil rights.

1987

Andrea publishes Intercourse, partially as a response to charges that, if she opposed pornography, then she must be opposed to hetersexual intercourse itself. The conclusions from this book have been used to falsely attribute to her the notion that all heterosexual intercourse is rape, something she denied. Instead, she argued that in a misogynistic, male-dominated society, the act of heterosexual intercourse is bound up with violence and with violating and subjugating women, and centering male pleasure. This subjugation becomes a core part of women's identity as women, and they come to desire it.

1997

Andrea publishes Life and Death: Unapologetic Writings on the Continuing War on Women. Along with an autobiographical essay on her life as a female writer, she tackles topics such as violence against women, pornography, prostitution, Nicole Brown Simpson, rape as a war tactic in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the École Polytechnique massacre and Israel. While she understood the need for Jewish people to have a homeland, Andrea opposed the occupation of Palestine and the subjucation of Palestinians.

April 9, 2005

Andrea dies in her sleep in her home in Washington D.C. at the age of fifty-eight. She had suffered ill health for years, writing "The doctor who knows me best says that osteoarthritis begins long before it cripples—in my case, possibly from homelessness, or sexual abuse, or beatings on my legs, or my weight. John, my partner, blames Scapegoat, a study of Jewish identity and women's liberation that took me nine years to write; it is, he says, the book that stole my health. I blame the drug-rape that I experienced in 1999 in Paris."

Earlier, when a newspaper reporter asked how she would like to be remembered, Andrea said, "In a museum, when male supremacy is dead. I'd like my work to be an anthropological artifact from an extinct, primitive society."