Celebrating Feminist Economist Devaki Jain during Women’s History Month

By:

Veronica S.Friday, March 17, 2023

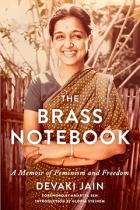

An acclaimed economist and researcher, Devaki Jain has penned dozens of influential books and essays championing social justice, democracy, and the empowerment of women. Now, in her insightful memoir, Jain provides a generous and vulnerable look at the early events that led her to reimagine the field of economics through a feminist lens. The Brass Notebook spans seven decades of Jain’s experiences as an Indian woman navigating academia, family life, and a remarkable career as a feminist economist. Highlighting the major political and personal events that shaped her life, and interspersed with diary entries, photographs, and intimate conversations with feminist scholars, this memoir documents the evolution of Jain’s thinking about feminism, liberation, and economic equity for working women.

Women’s Work

Written in lucid and compelling prose, the memoir moves nimbly between the personal and the political as Jain sifts through the pivotal moments of her childhood and adolescence. Jain’s early thinking about the unrecognized labor of women began with observations of her own family. Jain recalls that her mother’s youngest sister, Andal, was “a living example of unpaid family labor, and this was the pattern for all unmarried daughters or relatives—stigmatized and enslaved.”

Jain burrows deep into her past when she recalls the pressure and shame she faced from her family when she delayed marriage only to later marry outside of her caste. Jain also explores the ambivalence of motherhood as she attempts to balance her domestic roles along with her academic career. Lamenting the differences between her husband’s freedoms and her own, Jain reflects on feeling “trapped and resentful.” Nonetheless, Jain’s memoir is a celebration of the love that enveloped her family; she tenderly recalls her eldest brother Rajan as the source of her literary readings throughout her adolescence, her family’s safaris to the forests of south India, and the romance and devotion she often witnessed between her parents. What emerges from Jain’s candor about her family and domestic life is an enthralling story about grief, shame, love, pleasure, and bold defiance.

Navigating the Academy

Citing India’s independence as a turning point in her own coming of age, Jain went on to study at Ruskin College where the majority of students were working class and the atmosphere was deeply anti-colonial. After her time at Ruskin College, Jain returned to India in support of Vinoba Bhave’s bhoodan movement—the attempt to persuade landowners to give their land voluntarily to the landless. Working with the Indian Cooperative Union, she lived and worked in a village called Jharigaon while she helped reconstruct the area and develop it as a collective. These travels and experiences furthered Jain’s thinking about equitable distributions of wealth.

Jain continued her work in economics by pursuing a role as a research assistant for a Swedish economist at Oxford. However, when the professor who hired Jain later assaulted and fired her, the after-effects of the assault threatened not only her personal safety and self-confidence, but also her academic performance. Disillusioned with her own sense of freedom and shaken by the realization that working women are always at risk of exploitation, including sexual exploitation, Jain recollected her ambition and found solidarity with other women in the academy.

Working for Equality

Jain’s personal experiences of harassment and discrimination coalesced with her encounters with feminist thinkers such as Gloria Steinem, Iris Murdoch, Peter Ady, and Jenifer Hart to inform the feminist lens on her later economic research. Many of her historic accomplishments combined her expertise in statistics and economics with her personal investment in women’s labor. For instance, while conducting research for the Delhi-based Institute of Social Studies Trust, Jain traveled to Meghalaya and noted that working Meghalayan women were unable to make a living from the orchids and spices they were growing due to exploitative wholesalers. Jain designed and submitted proposals to the Planning Commission for funding and helped the women form cooperatives that would give them access to the profit of their own labor. In addition, Jain met Dr. Julius Nyerere, the activist committed to non-violence and the liberation of African nations, and she became the first woman to join Dr. Nyerere’s South Commission in the mid to late 1980s. Today, Jain’s involvement with the Republic of South Africa continues as she works with them to strengthen their economic base.

Most notably, alongside other scholars and activists, Jain developed DAWN (Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era) to develop a feminist economist framework that linked the situation of poor women to the macroeconomic and political framework of their countries and regions. This framework overturned the UN’s previous “ladders approach” that failed to connect status and macropolicies, and DAWN went on to present five panels in Nairobi at the UN’s World Women’s Conference in 1985. Jain’s projects provided crucial and innovative scaffolding in the field of feminist economics that persists today.

“The life of a free woman cannot be insulated from hurt,” Jain writes in the memoir. A necessary addition to feminist literature, The Brass Notebook captures the passion and determination of a woman in search of freedom for women everywhere and for herself.

An excerpt from The Brass Notebook is available below. Chapter 7, "Engaging with India," discusses Jain's fascinating work in the heady days of the cooperative movement with figures like Amartya Sen and the beginning of her career as a scholar and activist—while the looming expectations of marriage, domesticity, and children become more difficult to ignore.

Blog section: