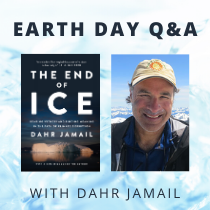

Earth Day Author Spotlight: A Conversation with Dahr Jamail

In celebration of the 50th Earth Day, we had a conversation with Dahr Jamail, author of The End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption. A finalist for the 2020 PEN/E.O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award, The End of Ice expresses both a deep love for the Earth and a frightening warning about its future. Jamail traveled around the world to the locations experiencing the most dramatic impacts of climate disruption, alongside some of the leading experts studying these locales, to investigate what lies ahead. Kirkus Reviews called The End of Ice “assiduously researched, profoundly affecting, and filled with vivid evocations of the natural world,” and Booklist praised it as “enlightening, heartbreaking and necessary.” This book—and what Jamail has to say about it—makes for essential Earth Day reading.

Dahr Jamail, a Truthout staff reporter, is the author of Beyond the Green Zone: Dispatches from an Unembedded Journalist in Occupied Iraq as well as The End of Ice. He has won the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism and the Izzy Award. He will be speaking at a virtual event with Town Hall Seattle on Thursday, April 30 at 7:30pm PDT. You can find more information on the event here.

* * * * *

What prompted you to write The End of Ice?

Dahr Jamail: Having moved to Alaska in 1996 and spending most of my free time in the mountains and on glaciers there, I was immediately and acutely made aware of the dramatic impacts of climate disruption that were already upon us. That deep experience remained within me for years, then ultimately led me to writing this book.

Why do you use the phrase “climate disruption” rather than “climate change”?

DJ: Because it is more scientifically accurate, as human-forced warming of the planet has literally disrupted the climate.

Why is hopefulness about the Earth’s future problematic?

DJ: Because hope is future- and other-based, and in that sense acts to relieve us of our personal agency. Additionally, we cannot begin to make the important decisions that we each need to make at this moment in history unless we have a firm grasp and acceptance of how dire our situation is. Hope serves as a disability in regards to our being able to see our current reality clearly. Only from a place of deep acceptance of the gravity of our times that is now upon us can we find the inspiration necessary to do the work that is before us.

You write about your conversations with researchers, field experts, and locals in each of these hot spots. Whose story stuck with you the most?

DJ: That is challenging to answer, as my conversations with all of them ignited insightful and often profound moments. The first one to come to mind is a conversation with US Geological Survey glaciologist Dr. Dan Fagre at Glacier National Park. After spending the day with me to show me the dramatic loss of glaciers in the park, Dan made the comment that the loss of Earth’s ice was happening so fast it was “a nuclear explosion of geologic change.” When I asked him how it felt to have to watch the thing he’d dedicated his life to studying, he told me, “It’s like being a battle-hardened soldier. But on a philosophical basis, it’s tough to watch the thing you study disappear.”

“Only from a place of deep acceptance

of the gravity of our times that is now upon us can we find

the inspiration necessary to do the work that is before us.”

Has our climate disruption changed since you first published The End of Ice? Have you noticed a change in the actions and conversations of our institutions and with individuals?

DJ: Climate disruption has accelerated dramatically since The End of Ice was published in January 2019. Since that time we’ve seen the record-breaking wildfires scorch the Amazon rain forest, record-breaking heat and wildfires sear Australia, a record-breaking melt year in Greenland, permafrost already thawing at a rate not expected for another 70 years, and now 2020 is predicted to be the warmest year ever recorded. Due to all of these things, the last year saw an explosion of awareness of the climate crisis, which of course has been a positive. Unfortunately, there has been little to no action on an emergency level required to cause serious mitigation or real adaptation measures by governments around the world . . . least of all in the United States.

We see the global shutdown for COVID-19, and the dramatic lowering of CO₂ emissions that has accompanied this. This is the kind of emergency response we should have had years ago regarding the climate crisis, and it would have to be sustained.

With the world on pause due to the coronavirus pandemic, does it offer any opportunities for mitigating climate disruption?

DJ: This would be the perfect opportunity to reorganize how things are done globally to prepare to live accordingly in a climate disrupted world. Food production must become localized, flying should only be for emergencies, all of our economic habits have to come into alignment with what is best for the Earth, rather than being based on how people can generate the most profit, or have the most convenience or fun. System change includes our psychology. The modern industrial economy has been a death knell for the planet’s ecology, and this stasis moment should be used to make the dramatic shifts into right-relations with life on Earth.

Since many of us are stuck indoors, are there any resources you would suggest that readers could visit to connect with and revel in the beauty of nature?

DJ: It starts with something as simple as taking walks. Look at the sky, find a stream or a river and watch the water flow. Sit beneath a tree and watch it move in the breezes. Look for birds and other wildlife. This is possible for most anyone, even in cities.

Online, for those who can’t get outside, the National Park Service has resources available for people to visit national parks and look at photographs and videos where they can find inspiration.

The most important thing is for all of us to remember that we are part of the Earth, and the Earth is part of us. How we treat each other is how we treat the Earth, and how we treat the Earth is how we treat one another. Once we bridge that separation that the western perspective had instilled in our culture, our behavior towards the Earth will change.

* * * * *