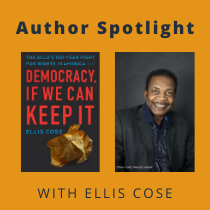

Author Spotlight: A Conversation with Ellis Cose

In the newly published Democracy, If We Can Keep It: The ACLU’s 100-Year Fight for Rights in America, renowned journalist Ellis Cose tells the story of an essential U.S. institution. For most of the country’s history the rights guaranteed by the Constitution were, as Cose describes, “like precious heirlooms: things to be admired but not necessarily put to use"—that is, until a movement of civil libertarians rose up to insist that America obey its own Constitution. Cose’s narrative begins with World War I and the Woodrow Wilson administration’s unconstitutional war on radicals, which led to the founding of the American Civil Liberties Union. From there he examines some of America’s most difficult crises from the Red Scare, the Scottsboro Boys’ trials, Japanese American internment, and McCarthyism, into the twenty-first century through the horrors of 9/11 and the saga of Edward Snowden, up to our present moment.

Democracy, If We Can Keep It is not just the story of the ACLU, but the story of the rights and freedoms that have come to define what it means to be American.

This year marks the American Civil Liberties Union’s centennial anniversary. In the interview below, author Ellis Cose reflects upon the ACLU’s one-hundred-year history to discuss the organization’s founding, its impact, and the state of civil liberties in the United States.

* * * * * * * * * *

How did a group of peace activists from World War I evolve into America’s most important group championing civil liberties?

Ellis Cose: Although the ACLU was established in 1920, the foundation was laid during a nearly five-year period that began in 1915, when those pacifists came together as the American Union Against Militarism.

The purpose of the AUAM was to keep the United States out of the European war. Obviously, they failed. Instead, once America’s involvement in the war became inevitable, the AUAM ended up working with conscientious objectors and defending the rights of critics of the war.

By 1920, the war was over, but America was still dealing with its consequences. The so-called Palmer Raids were in full flower, as Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer made a crusade of rooting out what he considered to be foreign radicalism. Hundreds of people remained imprisoned for having spoken out against the war. And the whole idea of free speech, although supposedly guaranteed by the First Amendment, was nothing but a dream.

The ACLU was founded during one of the most divisive moments of U.S. history. You wrote about how our unity was fragmented and how racism, xenophobia, and labor battles surged. What parallels do you see between then and our present moment? What lessons can we learn from history?

EC: The biggest lesson is that fear leads to repression. We saw that very clearly in the way the government squelched debate and free speech during the war. We saw it just as clearly with Trump, who used fear of a foreign so-called invasion to weaponize our policies against refugees, immigrants, and others he considered to be undesirable.

It’s important to recognize, however, that we are in a very different era than in 1920. Yes, the divisions were very deep back then, but they were along different lines than those you see now. The United States was emerging from World War I and also had just witnessed the Bolshevik Revolution and the rise of Communism. Americans were very much united around the war effort once we actually got involved in the war. Indeed, that very unity made it easy for this country to embrace suppression.

We also had huge racial divisions back then, propagated largely by whites determined to prevent Blacks from using the war, and the sacrifices Blacks had made for their war, to fight for equality. So right after World War I, white America declared war on its Black communities.

Some of the worst anti-Black riots in history occurred in the summer of 1919, which the NAACP called the Red Summer. Cities literally flowed with blood. Scores of Blacks were killed in Elaine, Arkansas. Many also were killed in Chicago, Washington, DC, and in other towns and cities across America. The riot in Chicago was set off by a Black boy wandering into the so-called white part of a beach. In DC, it was set off by apparently baseless rumors that a Black man had raped, or attempted to rape, a white woman. In Elaine, perhaps hundreds were killed—no one knows the true number. The white press attributed the violence to a Black uprising, which supposedly justified an invasion of the Black community by federal troops. In reality, the cause of white anger was an effort by Black sharecroppers to unionize and to get a fair price for their cotton.

You also had a labor crisis. Salaries had been depressed by a wartime salary freeze and workers wanted to catch up. Major battles ensued between unions and big business. There was a coal strike, a steel strike, and numerous other labor disruptions. Taking a cue from the suppression of radical thought by the U.S. government, big business presented itself as a champion of the American way of life—not unlike the way Trump has presented himself. Business portrayed unions as a tool of foreign Bolsheviks and other dangerous radical ideologies. The American press largely cheerleaded that effort. Black demands for better treatment, not surprisingly, were also attributed to evil, foreign influence. And the American public largely bought it. If there is a lesson in that, it has to do with how easily Americans are duped whenever the discussion becomes about “us versus them.”

Americans were not nearly as polarized then in terms of partisan politics. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, was ailing, so he did not run for reelection in 1920. Warren Harding, the Republican candidate, campaigned on a promise to return American to “normalcy.” He won in a landslide.

Trump’s campaign in 2016 was, perhaps incongruously, both about disruption and about returning America to greatness—which sounded a lot like taking it back to the past. But, in contrast to Harding, Trump barely won at all. Indeed, he actually lost the popular vote by an unprecedented margin of nearly 3 million. What Trump nonetheless managed to do was to weaponize fear of foreigners and minorities. He also weaponized fear of change. And that, for him, became a winning message—as it has been for countless American politicians across the decades.

The founders of the AUAM were veterans of those wartime battles. Although Roger Baldwin was not an AUAM founder, he became one of its most important leaders. Given its origins, it made sense that the AUAM eventually gave birth to the ACLU, which focused on what they then saw as the principal threat to democracy—internal repression, particularly of speech. Baldwin became the executive director by acclamation.

"The biggest lesson is that fear leads to repression.

We saw that very clearly in the way the government squelched debate

and free speech during the [first world] war. We saw it just as clearly with Trump"

Is there a particular moment you can point to when public consciousness shifted, and the average citizen came to expect the political and social freedoms afforded by the Constitution?

EC: I think that awareness came in stages and is an ongoing process as new generations of Americans determine what they stand for and discover what the Bill of Rights means to them. In the early days, the ACLU had very little money. Many of their efforts amounted to public education stunts. They would send people to towns that had ordinances prohibiting individuals or groups from publicly speaking without getting the permission of police chiefs or politicians. The ACLU would deliberately violate such laws with public readings of the Constitution. That public education effort became a big part of what they did.

The ACLU was also involved in a series of landmark free speech cases, going back to the early 1920s. The ACLU lost many of those cases. Nonetheless, they ended up making a public argument that eventually resonated with America that freedom to speak was a right—not a privilege. There was an especially important case, Gitlow v. New York, decided in 1925, that led the Supreme Court to declare that the states were bound by the Bill of Rights—and therefore were required to recognize the right of free speech. This is the so-called Incorporation Doctrine, where the court made clear that the Fourteenth Amendment applied to the states, and that states were therefore obligated to honor the Bill or Rights. That obligation previously had not been so clear, so it was an epic decision. But it was only one of many that brought home to Americans that we are entitled to speak our minds.

In what ways did Roger Baldwin’s personal progressive views become entwined with how Americans think of free speech?

EC: Baldwin was pretty much a free speech absolutist, which was one of the reasons he supported the rights of Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan to speak. But he also came out of a very progressive tradition, as you note. He genuinely believed that the right to speak was what protected democracy and that exercising that right would inevitably lead to progressive policies. He never foresaw a time when the political right would attempt to hijack the right to free speech for itself. He certainly never foresaw the Citizens United decision by which the Supreme Court, in 2010, essentially blessed the notion of corporations pouring untold billions into political races. Corporations were as entitled to free speech protections as any citizens, decided the court, meaning their right to back candidates and speak out and spend money was somehow equivalent to the right you and I might have to speak out. It’s not exactly clear how corporations became citizens, but they somehow apparently did.

Baldwin could not have imagined such a time—nor could other Americans who were seduced by his particular view of free speech. They tended to see free speech as a tool of the progressive movement, not of the rich corporations or the regressive right.

"The ACLU was also involved in a series of landmark free speech cases, going back to the early 1920s.

The ACLU lost many of those cases. Nonetheless, they ended up making a public argument

that eventually resonated with America that freedom to speak was a right—not a privilege."

Was Baldwin a socialist?

EC: In his early days, Baldwin was clearly captivated by certain aspects of socialist ideology. He was a big fan and friend of self-declared anarchist Emma Goldman. Much of his early rhetoric was clearly influenced by socialist ideology. He felt that workers, in time, would inherent the earth and control the means of production. After a visit to the Soviet Union in the 1920s, Baldwin wrote a book defending the Soviet system. But as he learned more about that system, his views changed, and he ultimately (like Goldman) became a critic. Indeed, in 1940, he presided over the effort to eject Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the ACLU’s only Communist board member, from its board. Flynn was very popular with progressives, so that became one of the most divisive chapters in ALCU history.

Prior to that, Russia had entered into a pact with Nazi Germany, which Baldwin considered a bridge too far. So he was eager to publicly disassociate himself from Russia and its ideology. The ACLU was also being criticized by congressional committees and others for its supposedly communist or socialist ties. Baldwin felt it essential to distance himself from such views, which he diligently did. He ultimately ended up being essentially a social democrat or democratic socialist. He believed in a democratic system with a strong government that also sanctioned private ownership and capitalism.

What role has the ACLU come to play in social and protest movements in the United States?

EC: My book is largely a history of social protest movements in America. That is the case for one simple reason: the ACLU, in one way or another, was deeply involved in virtually all those movements. If you look at the campaign around free speech, racial equality, civil rights, interracial marriage, gay marriage, the Vietnam War, the draft, privacy, press freedom, the list goes on and on, you will find the ACLU was almost always somehow involved, and often at the forefront. That continues to this day when, early on, the ACLU positioned itself in opposition to Trump’s anti-democratic and racist policies.

What is the most fascinating thing you discovered in the ACLU archives that didn’t make it into the book?

EC: That is hardly a fair question for an author, who is bound to assert that all of the most fascinating things are in his or her book. In fact, I think they pretty much are in this case. What’s left out? I did not wallow in personal feuds and peccadilloes, though I do deal with some of those in the book. But if I was to point to one thing that I didn’t bother including and that I found personally disappointing, it would be Baldwin’s views when it came to Black board members. He criticized them for being too focused on the fight for minority rights, which to him was a sign of their inability to take a broader view. I think that was ridiculous and a reflection of his freedom, as a privileged white person, to ignore the centrality of racial oppression to American life.