9 Women Civil Rights Leaders to Celebrate this Black History Month

Most Americans know of Rosa Parks, the Black woman who famously refused to give up her seat to a white person on a bus in Alabama, and helped to ignite the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s. Equally well known is Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King, Jr., and a formidable force in her own right. But a majority of Americans would have a hard time naming other important female leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, although there were many more than two. In Lighting the Fires of Freedom, newly published in paperback, Janet Dewart Bell weaves together the deeply personal and untold accounts of nine of these women to shine a light on their often overlooked achievements.

We are thrilled to introduce the nine women profiled in Bell’s groundbreaking oral history and hope you’ll want to find out more. Each of them answered the call for freedom with valor, commitment, and passion. They were principled and steadfast. They lit the fires and showed the way.

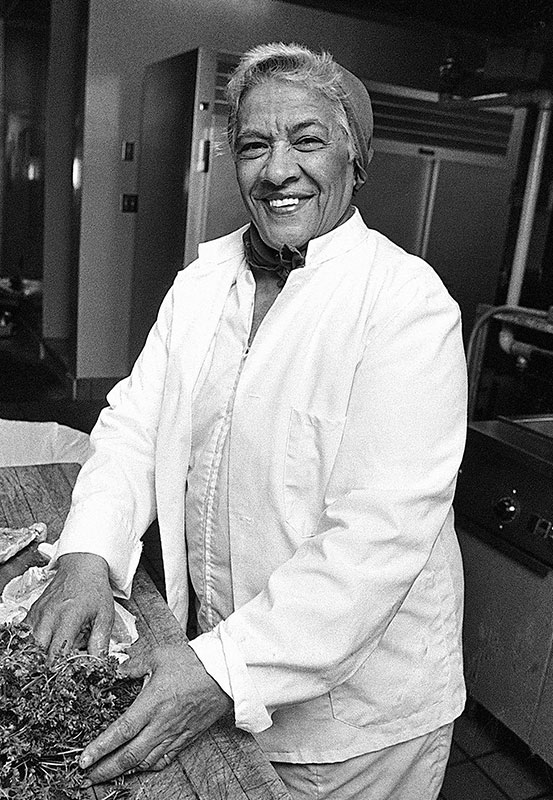

Leah Chase

A celebrated chef and community leader from New Orleans, she helped to bring about change simply by doing what she does best: bringing people together over good food and providing an atmosphere of warmth and caring. During the Civil Rights Movement, she hosted Martin Luther King, Jr., Thurgood Marshall, members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating committee, and many others of all races and backgrounds at her family restaurant, Dooky Chase. Her interracial gatherings were by their very nature in defiance of the South’s segregation laws. Yet her restaurant was never raided or shut down for her then illegal activities, perhaps because she and her family were held in such high regard throughout New Orleans. She passed away in 2019 at the age of ninety-six.

Dr. June Jackson Christmas

One of the first African Americans to graduate from Vassar College, she championed the cause of interned Japanese Americans during World War II. As a trailblazing psychiatrist, she specialized in community mental health care, especially for low-income African Americans, and served as mental health commissioner for New York City under three mayors. With her husband, Walter Christmas, she waged a personal fight against housing discrimination that changed New York City law. During the Civil Rights Movement, she and her husband opened their New York City home to provide respite, as well as counseling and fundraising support, for civil rights workers from the South.

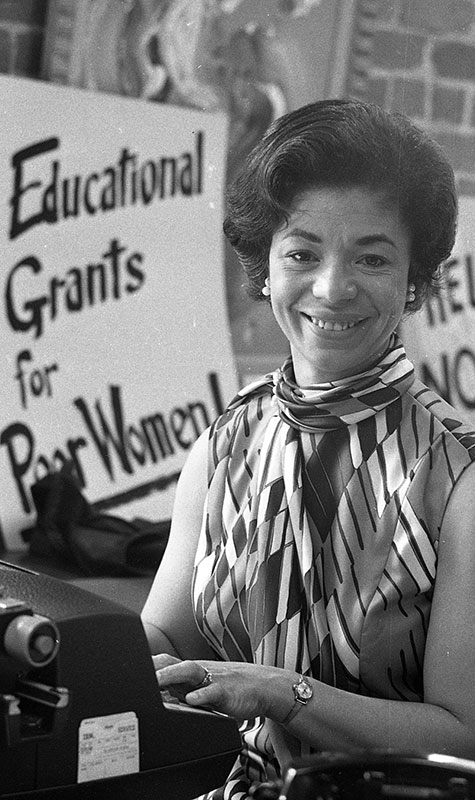

Aileen Hernandez

She began her activism as a student leader at Howard University during World War II in then legally segregated Washington, D.C. In 1964, she became the first woman and the first African American to be appointed to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), from which she resigned because of its unwillingness to address sexual harassment. She was the first African American president of the National Organization for Women, which she left after it elected an all-white officer slate. She later co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus and Black Women Organized for Political Action. She also served on the San Francisco Human Rights Commission. A pioneer in issues concerning intersectionality of race, sex, and class, she was socially active for her entire life, until shortly before she died at age ninety in 2017.

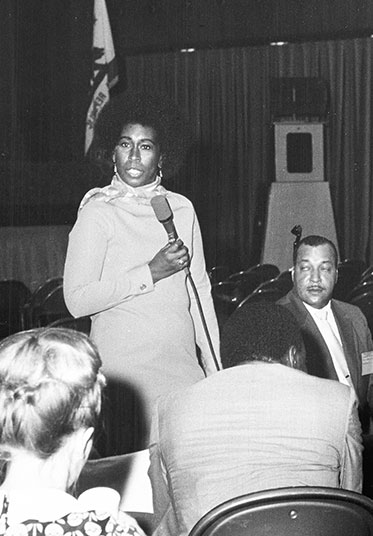

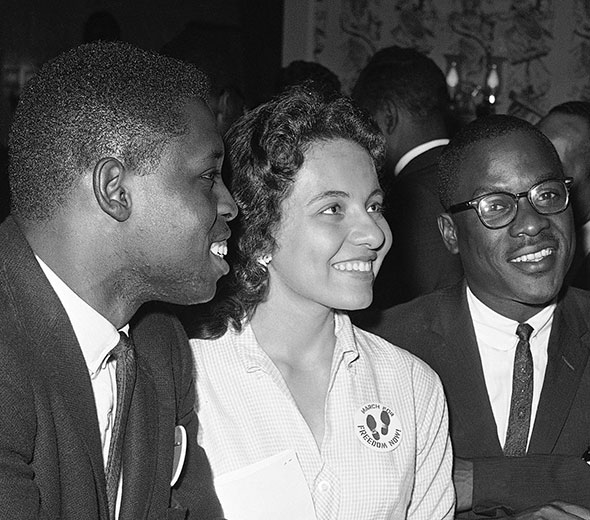

Diane Nash

She led the Nashville Sit-in Movement, which preceded the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and coordinated the Birmingham, Alabama to Jackson, Mississippi Freedom Ride after the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) was forced to discontinue it. Her tactical and unwavering support of the Freedom Riders was critical to their success throughout the South. In 1962, Martin Luther King, Jr., nominated her for an award from the NAACP’s New York branch, acknowledging her as the “driving spirit in the nonviolent assault on segregation at lunch counters.” After her work with the Freedom Riders, she returned to her hometown of Chicago and became an advocate for fair housing.

Judy Richardson

During her freshman year at Swarthmore College, she joined the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) group on campus that was organizing against segregation in nearby cities. She left Swarthmore after her freshman year to join the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Among many other duties, she helped to monitor SNCC’s 24-hour, 800-like telephone line—literally a lifeline for SNCC activists. She later co-founded Drum and Spear bookstore and Drum and Spear Press in Washington, D.C., both of which were instrumental in publishing and promoting Black literature. She later became the series associate producer and education director for Eyes on the Prize, the seminal fourteen-hour PBS series on the Civil Rights Movement. She continues to lecture, write, and conduct teacher workshops about the Movement then and now.

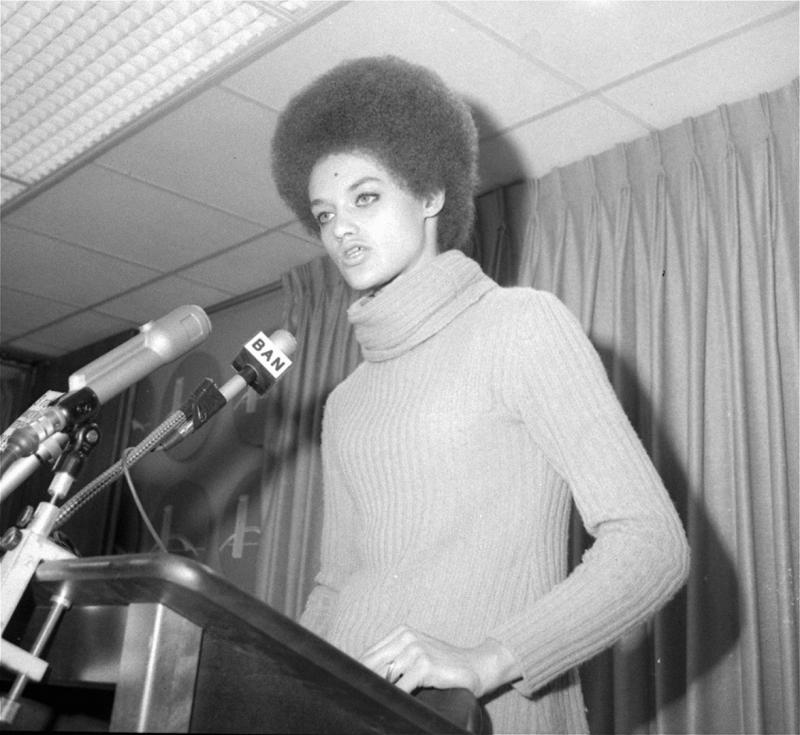

Kathleen Cleaver

Her activism was inspired by her parents and their circle of friends and colleagues in Tuskegee, Alabama, where service and fighting for one’s rights were expected. She was the first woman to serve on the Central Committee of the Black Panther Party, where she developed communications strategy and outreach to media. She and her then-husband Eldridge Cleaver spent four years in exile from the United States in Algeria and Korea, where their children were born. Kathleen Cleaver returned to the United States in 1973, and with her husband created the Revolutionary People’s Communication Network. She later graduated from Yale University summa cum laude and went on to Yale Law School, graduating in 1989. She clerked for federal judge A. Leon Higginbotham and became a law professor.

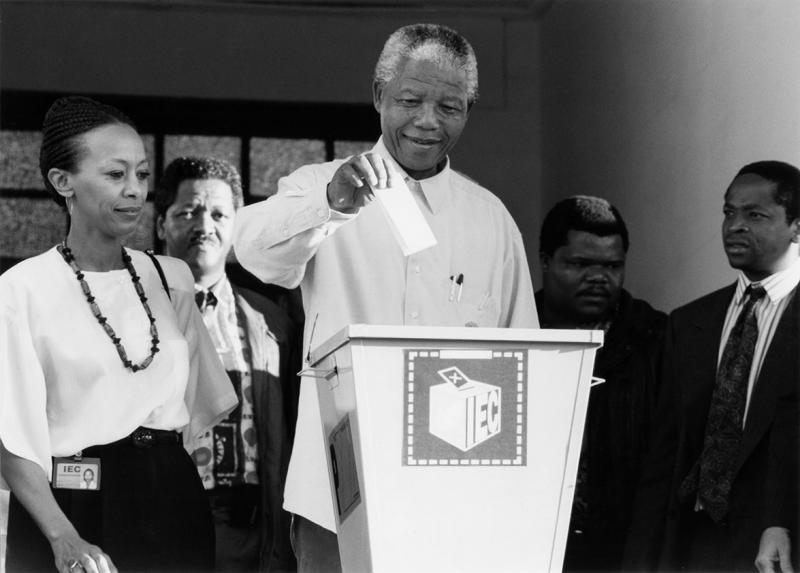

Gay McDougall

The first African American to integrate Agnes Scott College in Georgia, as well as a graduate of Yale Law School and the London School of Economics, she forged a storied career in international human rights. The first United Nations expert on minority issues, McDougall was instrumental in the Free South Africa Movement’s protests against apartheid and was later named as one of five international members of the South Africa governmental body established to administer the country’s first democratic, nonracial elections, resulting in the election of President Nelson Mandela. She accompanied Mandela when he voted for the first time and was the first American to be elected to oversee the United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. In 2015, the government of South Africa bestowed on her their national medal of honor for non-citizens for her extraordinary contributions to ending apartheid.

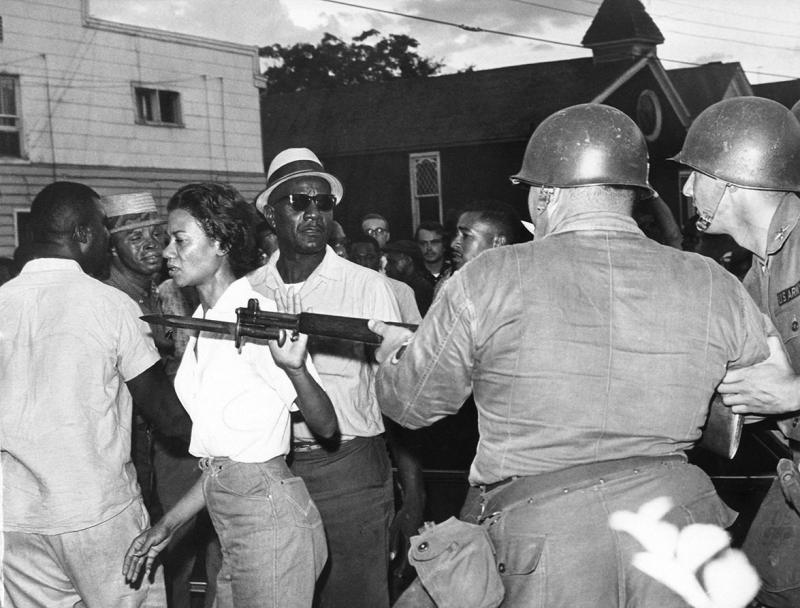

Gloria Richardson

Born in 1922, she was an older adult during the Civil Rights Movement, who first became involved to support her teenage daughter and other youth demonstrators. Unlike the gentle public persona of Rosa Parks, Richardson was openly militant, leading street protests and questioning nonviolence as a tactic. Her stance inspired later efforts of the Black Panthers and others who adopted more militant responses to social injustices. Because of the successful protests that she led as head of the Cambridge (Maryland) Nonviolent Action Committee, Ebony magazine named her “the Lady General of Civil Rights.” She later moved to New York City and worked in human services. Now in her nineties, she supports the youth of the Black Lives Matter movement and has not lost her passion for justice.

Myrlie Evers

Most Americans, watching her deliver the invocation at the second inauguration of President Obama in 2013, would likely be surprised to know of her heroic history. As the wife of Medgar Evers, Mississippi’s first NAACP field secretary, she knew the dangers of activism for racial equality. She and her husband were partners in every way. Their home was firebombed and Medgar was assassinated in their driveway. Maintaining her commitment to civil rights and public service, she waged an unsuccessful campaign for congress and later became the first Black woman to serve on the Los Angeles Board of Public Works. At the age of sixty-two, she became the chair of the NAACP and helped to reinvigorate the organization. Meanwhile, she vigilantly pursued justice for the assasination of her husband, a three-decade commitment that ended in 1994 when the killer, an avowed white supremicist, was convicted of murder.

Learn more about these women, their stories, and their contributions to the Civil Rights Movement and beyond in Lighting the Fires of Freedom.