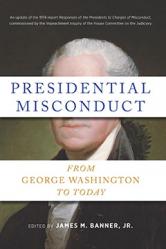

AUTHOR SPOTLIGHT: James M. Banner Jr.

Monday, July 15, 2019

Mention the words “Watergate,” “Iran-Contra,” or, more recently, “Russia” at a dinner party and watch the room explode with debates over what actions are impeachment-worthy and who is more corrupt than who. But as the esteemed historians in Presidential Misconduct illustrate, every president has contributed their fair share of scandals and bad behavior to American political memory. In a series of illuminating essays that covers each presidency from George Washington to Barack Obama, this anthology exposes the ups and downs of corruption of the executive branch.

We sat down with Guggenheim Award–winning historian and editor of Presidential Misconduct, James M. Banner Jr., to discuss what constitutes genuine corruption, whether he thinks we are currently in a constitutional emergency, and what he wants readers to take away from this book. Presidential Misconduct is in stores now.

Why did you feel that an updated version of the 1974 Impeachment Inquiry report, in this version titled Presidential Misconduct, was necessary? And why now?

JB: The 1974 report was originally completed at the request of the Impeachment Inquiry of the Committee on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives during the Watergate crisis forty-five years ago. Richard Nixon was the first president to use the Oval Office to purposefully break the law and cover up his administration’s misdeeds. Not until now has another president orchestrated legal and constitutional misdeeds from the White House. Nor has another president defied the constitutional responsibilities of Congress, heaped contempt on the press, raised expression to an unprecedented level of cringe-inducing vulgarity, and acted in ways that sully the honored name of the nation whose presidency he has gained. It is difficult to acknowledge him in the line of such great figures as George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His baneful acts—some proven, some not yet conclusively demonstrated by available public evidence—make for nothing less than a constitutional crisis and a profound threat to governance.

So while there have been known cases of misconduct by the executive branch since as early as Washington’s administration, only once before now have presidential misdeeds threatened constitutional government and venerable norms of leadership and public behavior. It was therefore the seriousness of Donald Trump’s threat to normal constitutional processes that, in 2018, led a group of historians to conclude that a crisis of this magnitude warranted an update to the 1974 report. Presidential Misconduct is the result.

In carrying out our task, both the authors of the original report, of which I was one, and those who have now contributed additional accounts of presidential misbehavior through the Obama administration, have sought simply to provide a factual record of presidential wrongdoing over roughly 230 years. It is a record by which readers can independently assess, against the long record of American presidencies, how the present crisis compares with previous ones. Whatever our political leanings, the authors of the 1974 original and this new version have resolutely kept away from indulging in partisan or ideological controversies or entering into scholarly debates. Our intention has been solely to convey to our fellow citizens a factual record of presidential misdeeds and responses to charges of such misdeeds going back to the founding of American constitutional government. It’s up to readers of this historical record to make of it what they can in their search for understanding of the nation’s present crisis, one that cannot be fully understood without knowledge of earlier malfeasance.

You are careful to establish a distinction between “genuine corruption” versus “political and policy disputes.” Can you give a current example that illustrates this difference and why the distinction is important?

JB: Political differences and disputes over domestic and foreign policy are the meat and potatoes of public life in a representative democracy like ours. Under the American system of government, argument over ends and means—“political and policy disputes”—cannot and must not be criminalized. They are natural and legitimate.

The current debate over immigration is a perfect example of a political and policy dispute that does not involve major proven corruption. (The debate does, of course, involve legal questions that are under judicial scrutiny; but those legal disputes don’t threaten the integrity of basic constitutional principles.) There is a no more deeply felt issue in all American history than this one, an issue never easily or conclusively solved, for it involves the very origin story of the United States. In fact, the significance of immigration has at no time been absent from American shores—not since Native Americans faced the arrival in the Western Hemisphere of Europeans. Since then, Americans have debated the issue of immigration. Thus even when Americans are engaged in what currently is a stand-off over how to think about and control immigration to the United States, they are engaged in a historically normal political and public dispute. An administration’s efforts to regulate immigration at the nation’s borders are entirely warranted. These efforts do not constitute misconduct; they become misconduct only when efforts to control immigration entail breaches in existing legal rules and in the ethical standards set down by legislation and recurring practice.

You write, “Until Nixon’s administration, none of the corruption and misconduct detailed in this book precipitated a constitutional emergency.” Do you think that the conduct of the Trump administration qualifies as a “constitutional emergency”?

JB: By definition, a constitutional emergency exists when a president doesn’t abide by the laws of the land. It also exists when the provisions of the Constitution, as interpreted by the courts and as accepted from long practice, are either ignored or prove to be ineffective in halting illegal and corrupt behavior. In that sense, yes, we are in the midst of a constitutional crisis.

On what grounds do I assert this? First of all, the president seems heedless of basic constitutional provisions. While it may require the courts to determine, for example, to what extent a president can refuse to comply with congressional subpoenas for documents, it constitutes either ignorance or open defiance of the Constitution to say, as President Trump did in early June 2019, that people might demand that he remain in office beyond his second term if he were re-elected. Even though it’s unforgivable in a president of the United States to be ignorant of the Constitution, ignorance isn’t unconstitutional. But acts based on ignorance of the Constitution can be. President Trump seems unaware that the Constitution limits presidents to two terms, whatever “people” demand, and that it would require an amendment to the Constitution to make more than two terms in office legally possible—a goal not achievable in our system overnight or by acclamation. To suggest otherwise invites Americans to ignore the Constitution. Such a suggestion is, on its face, contrary to the presidential oath to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Second, the administration has accumulated a clear record of obstruction of justice, defiance of congressional power, witness tampering, suppression of evidence, money laundering, tax evasion, attempts to skirt the clear intention of the Emoluments Clause of the Constitution, and additional related offenses. When taken together, these assaults on the rule of law constitute one of the most severe assaults on American law and governance since the commencement of American constitutional government. If these charges against the Trump administration don’t qualify as a constitutional crisis, nothing does.

You write, “[A]s this book reveals, remedies for illicit and illegal conduct by presidential administrations have had a mixed record of success.” What are your thoughts on how we, as citizens subject to consistent executive corruption, can hold American presidents responsible for their actions?

JB: Public vigilance—“eternal vigilance,” in Thomas Jefferson’s celebrated words—has proved no guarantee of protection against illegal and corrupt executive branch behavior. But here’s where the genius of an open society comes into play—Americans must act in the spirit of Jefferson’s faith that we must not be “afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.” In this case, the instruments of truth-finding must, as always, be the American people acting individually and collectively; the free press and its protections under the First Amendment; members of both houses of Congress and of the judiciary; officials of the “lesser” jurisdictions of states, counties, and municipalities in our federal system; and the voluntary organizations that exist at the center of American society. Yet as this book makes clear, the people as well as the public and private institutions that Americans have created cannot always prevent illegality and corruption. Juries fail to convict, and miscreants slip out of investigators’ grasp or are pardoned after conviction. Members of the press are foiled by legal and other obstacles in their search for the story. And public figures and office holders quail before the prospect of defeat at the polls for standing up for principle instead of running for political cover.

But it’s essential to notice that, even with such failures, public affairs have always recovered from corruption and threat, and the republic still stands. It’s likely to do so in the future as long as citizens remain informed and knowledgeable, make prudent judgments at the polls, support the institutions that compose American government and society, and hold their public officials accountable for their votes and actions. That’s what’s meant by “eternal vigilance.” There’s every reason to be optimistic that clear-eyed attentiveness to the principles and vision upon which the nation was founded will carry us through. But it’s up to each one of us to protect those principles and that vision to the best of our ability.