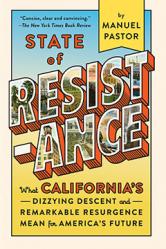

Manuel Pastor’s State of Resistance Featured on Cover of New York Times Book Review

The April 29 cover issue of the Book Review prominently features a rave review of State of Resistance: What California’s Dizzying Descent and Remarkable Resurgence Mean for America’s Future by Atlantic journalist James Fallows, who calls Pastor’s book “concise, clear and convincing.” The review goes on to say that State of Resistance “contends that the redemptive arc of modern California’s history offers both cautionary and constructive guidance on a vision for the country as a whole.”

How California Turned Into a ‘State of Resistance’

By James Fallows

New York Times

April 23, 2018

For a few decades after World War II, California seemed a showcase of what America could and would become. From Hollywood, Disneyland and the Beach Boys’ surf cities, its pop culture radiated eastward across the continent, and beyond. Its freeways and sprawling suburbs seemed to represent the new American residential model. Its ambitions for public parks and education were stupendous. Within a five-year early-1960s span during the sun-king administration of Gov. Pat Brown, father of the current Gov. Jerry Brown, the University of California system opened three new campuses: at San Diego, Irvine and Santa Cruz, all now major research centers.

In its promise of fresh starts and new opportunities, California was to the rest of the country what America, in its best version, was to the world. The booming economy, sunny (and not yet smog-drenched) skies, and shiny new schools and roads drew millions of new residents to the state after World War II (including my own parents, who moved from suburban Philadelphia, where they grew up, to the Inland Empire of Southern California, where they raised my siblings and me). Kevin Starr, who as state librarian became California’s most influential chronicler, signaled the state’s symbolic role by calling his multivolume history “Americans and the California Dream.”

Then came the long slide of discontent and dysfunction and decline. Racial unrest, police violence, multiple tax revolts, a state government increasingly hamstrung by “reform” measures from the early 20th century that had turned into sources of paralysis — all of these fed a sense of promise gone bad. In the early 1990s, California suffered an outsize share of the nationwide job loss that was the basis for Bill Clinton’s “It’s the economy, stupid” 1992 campaign. As Manuel Pastor points out in “State of Resistance,” half of all American job losses in those years were in California alone. Into the 2000s, the leading assessments of the state’s condition had titles like “Paradise Lost,” by Peter Schrag, and “The California Crackup,” by Joe Mathews and Mark Paul. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who became governor in 2003 after the luckless Gray Davis was kicked out in a recall vote, ended his term in 2011 with the budget in enormous deficit. Around that time Starr said that his homeland was on the verge of becoming “the first failed state in America.”

Less than 10 years later, California still has serious problems, but over all its prospect is the envy of most other states. Its success is uneven and, in Pastor’s term, “tentative,” with obvious challenges that range from class-based inequities in its richest cities to environmental sustainability for the state as a whole. But Schwarzenegger’s successor, Jerry Brown, will end his fourth and final term as governor with a large budget surplus. (His four terms have not been consecutive: Brown was, famously, also Ronald Reagan’s successor as governor more than 40 years ago.) One American in eight now lives in California, and it accounts for a larger share than that of the country’s output, innovation, job creation and wealth. While other state legislatures fight to retain gerrymandered political maps and enact voter-suppression schemes, California took the lead (under Schwarzenegger) in getting rid of gerrymanders, a movement Schwarzenegger himself is now trying to extend across the country.

California has of course also become the Democratic Party’s most important stronghold. In 2016 Hillary Clinton carried California by well over four million votes — and ran behind Donald Trump by more than a million in all the other states combined. This distinct political identity naturally feeds the impression, among progressive admirers and conservative critics alike, of California as a realm apart. So do the declarations by Brown and his attorney general, Xavier Becerra, of their commitment to environmental and immigration policies at odds with Trump’s.

Positions like these amount to the “State of Resistance” of Pastor’s title, but the book’s argument is actually the opposite of what “resistance” might imply. Instead, Pastor, a sociologist at the University of Southern California, suggests that at just the moment California seems most out of sync with national trends, it is in fact regaining its role as bellwether and pioneer. “The country needs resistance to be sure,” he writes, “but it also needs a vision of what America can become.” In his book, which is concise, clear and convincing, he contends that the redemptive arc of modern California’s history offers both cautionary and constructive guidance on a vision for the country as a whole.

Pastor sets out his story in three acts — rise, fall, recovery — each of which offers surprising insights for readers outside the state (and many inside as well). In describing the post-World War II years of expansion, which took place under governors of both parties, he emphasizes how heavily they involved public spending and investment — roads, schools, parks, both advanced research universities and numerous community colleges — and how much they shared a goal of preparing the state for new arrivals and future citizens. “California in the 1950s and 1960s was precisely the sort of demonstration project for an active government that many conservatives seem to fear at a national level,” he writes. “The real secret to California’s once and future success was exactly its agreement on a social compact in which the public and private sectors worked to create paths upward for both those who were in the state and those who were to come.”

The unhappy decline that constituted the second act was, in Pastor’s view, an uncannily precise preview of the economic, social and political discontents that now embitter our national politics. Deindustrialization hit California as hard in the 1980s as it hit any place in the Midwest. (Forty percent of the lost American manufacturing jobs in the early 1990s were in this one state.) Ethnic change was much more rapid. Pastor points out that between 1970 and 1990, the share of California’s population that was foreign-born rose from 9 percent to 22 percent. This was distinctly different from the rest of the country, where the foreign-born share rose in the same period from around 4 percent to just over 6 percent, and it led to what Pastor calls the “racial generation gap.” That is, a politically and economically powerful older generation, mainly white, resisted paying taxes to build schools and parks for a younger generation that was mainly nonwhite.

The result, Pastor says, was a several-decade escalation in the politics of fear, austerity and resentment, which harmed the state while also driving the California Republican Party further right, and eventually out of power. From Reagan through Schwarzenegger (with the exception of Jerry Brown), Republicans dominated the governorship of California. Now Republicans hold no statewide office at all. Of California’s 53 congressional seats, only 14 are in Republican hands, a number almost certain to go down after this year’s midterm elections.

Then we have the recent years of recovery, about which many reports (including some I have written) emphasize the savvy of Brown and his team. Pastor stresses instead two structural favors. One was a return to the collaborative public-private ventures, with an emphasis on long-term investment, that marked the state in its highest-growth years. Even today’s center of extreme private wealth, the Bay Area tech industry, illustrates the point, Pastor says. Its leaders recognize that they and the state rise or fall together. Because they “often see themselves in a sort of collective ecosystem that allows for individual success,” within this zone of hyper-capitalism “there has been a sense, now somewhat eroded by growing internationalization, of business responsibility for stewarding the region.”

The other factor in the modern rise, he emphasizes, is on-the-ground social movements: by labor unions, by immigrants and immigrant-rights advocates, by students, by Latino or African-American groups, and by others determined to offset corporate power with their organized voting and protest strength. Pastor is an academic sociologist, and this part of his book is written more in sociologese than the rest, including its extensive discussion of “intersectionality,” the overlapping effects of barriers of race, gender, class and other inequalities. But it ends with a list of practical lessons that can be drawn from California’s recent history to the national politics of coming years. One of these involves appreciating the geographical breadth a progressive movement can have. In California terms, this has meant fielding candidates and motivating voters in the conservative inland regions as well as along the coast. The national counterpart would be Democrats contesting races even where they seem to have no chance. Another lesson suggests progressive groups build alliances with business leaders, as in Silicon Valley.

“America now looks like California at its lowest point,” Pastor says. He offers a guide to a possible path back up.