AUTHOR SPOTLIGHT: Bernice Yeung

Bernice Yeung is an award-winning journalist for Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting covering race, gender, and issues related to violence against women. In 2013, Yeung was part of the national Emmy-nominated “Rape in the Fields” reporting team, which investigated the sexual assault of immigrant farmworkers. The project won the Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award and the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, and it was a finalist for the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting. Yeung was a 2015–2016 Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan, and her work has appeared in the New York Times, SF Weekly, California Lawyer magazine, the Seattle Times, Mother Jones, and The Guardian, as well as on KQED Public Radio and PBS Frontline. Yeung has a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University and a master’s degree from Fordham University, where she studied sociology with a focus on crime and justice. She resides in Berkeley, California.

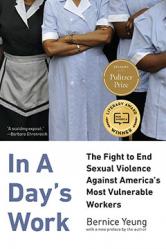

The New Press sat down with Yeung to discuss her new book, In a Day’s Work: The Fight to End Sexual Violence Against America’s Most Vulnerable Workers, a debut from “a reporter deeply committed to her sources and her material” (Publishers Weekly). With humanity and depth, Yeung takes us on a journey across the country, introducing us to women who came to America to escape grinding poverty only to encounter sexual violence in the United States.

“In a Day’s Work is a must-read for all who believe time’s up on abusive employment practices for all workers. Yeung shows us through these courageous stories that the time to change the balance of power is now.”

—Saru Jayaraman, author of Behind the Kitchen Door

In a Day’s Work centers on the experiences of women who came forward to report sexual harassment and assault. The people who helped them (workers at nonprofits, lawyers, legislators, and others) were often women of color themselves. Was that important?

BERNICE YEUNG (BY): I don’t think that race or ethnicity should matter when it comes to preventing or tackling issues like sexual violence, but I do think that because many of the advocates featured in this book are women of color or came from immigrant families, they were able to draw from a shared or familiar experience that was meaningful for all sides. It was clearly helpful that the advocates were familiar with the realities of the immigrant experience so that they could comprehend the cultural or logistical nuances of how these crimes are perpetrated and why the victims had abided in silence. For the workers, it seemed that the prospect of discussing an ugly incident was made easier by working with someone who literally spoke their language and who had insights into the circumstances under which they had to make difficult, if not impossible, decisions.

What steps can employers of low-wage workers take to make workplaces safer for the women in these “hidden” industries? What have the women you’ve spoken to in your reporting told you would make a difference?

BY: What decades of social science research has shown us is that when it’s clear that sexual harassment is not tolerated on the job—whether because the organizational culture frowns upon it or because the leadership has been outspoken on the issue—there will be less of it. So employers and companies that are committed to reducing sexual harassment have to provide sincere and meaningful signals that they take sexual harassment seriously. This can be done through clear policies that spell out that sexual harassment is not tolerated, and that create multiple ways for workers to report harassment in a way that is safe and straightforward. But policies and procedures are empty if there’s no action behind them. The organization and its leaders also need to walk the walk.

Beyond that, effective reforms will need to be industry-specific and they should focus more on prevention and less on filing complaints after the fact. For example, night shift janitors have suggested that working in pairs or during the day could minimize some risk of workplace sexual violence. In farm work, organizations like the Fair Food Program have created an external auditing and training system that helps send the message that sexual harassment is not acceptable. Domestic workers have said hiring agencies could take a more proactive role in helping address sexual harassment in their industry.

A still from Rape on the Night Shift, a 2015 documentary by Frontline (PBS), Univision, the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley, Reveal, and KQED that investigated sexual assault in the janitorial industry, and sparked legislation in California. It is streaming at pbs.org/frontline.

Immigration authorities are making more arrests, and the anxieties around deportation loom large in immigrant communities. Those working in janitorial, domestic, and farm work often say that undocumented status is a reason they don’t report workplace abuses. Do you think it’s become more difficult for women in these industries to report sexual harassment?

BY: The undocumented women featured in this book initially hesitated to report workplace abuses for a whole constellation of reasons. Like many victims, they felt ashamed and they didn’t think anyone would believe them. As newcomers, they weren’t familiar with U.S. labor laws that prohibit sexual harassment. Those who were undocumented immigrants also worried that they would be deported or lose their jobs by making a complaint about sexual harassment.

Those concerns around deportation have grown. In my recent reporting on immigrant communities, the anxieties around deportation and being separated from their kids here in the United States are real. Covering sexual harassment among immigrant workers was challenging five years ago when my collaborators and I embarked on this line of reporting and I imagine that it has become even more so now.

But threatening to deport or fire a worker for complaining about a workplace abuse could be considered a form of illegal retaliation. And it’s important to note that there has been a long history of protecting immigrant victims of crime from deportation. Federal laws that received bipartisan support provide special visas for noncitizen victims if they help with an investigation or prosecution of a crime. As one retired police chief said during a 2011 congressional hearing, the visas are “an invaluable vehicle to work closely with victims to prevent crime, save lives, and hold violent offenders accountable—strategies consistent with the philosophy of community policing.”

Despite recent shifts in immigration enforcement and policy, these laws remain in place. More work could be done to make both local law enforcement and abused workers aware of the policies that exist to protect victims of crime, regardless of their status.

Maricruz Ladino’s story was featured in Rape in the Fields, a 2013 documentary by Frontline (PBS), Univision, the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley, Reveal, and KQED that investigated the sexual assault of female farmworkers. It is streaming at pbs.org/frontline.

There’s been a backlash to the #MeToo movement. What do you think of the swift professional (and personal) consequences to perpetrators in some of these cases?

BY: One of the most notable aspects of the #MeToo movement is the way in which high-profile women have been able to demand and receive accountability when they have publicly complained about sexual harassment. However, when a complex social problem is viewed through a narrow set of cases, a backlash is inevitable.

I understand and agree with the desire for consequences to be commensurate with behavior, but I’d suggest that those who are reacting negatively to the responses that these complaints have received could consider sexual harassment cases in greater context.

In many of the cases attracting media attention, we aren’t privy to how those decisions were made. So while we know of the very public allegation and the much-buzzed-about outcome, we know very little about what the company’s internal process or investigation looked like.

Quick and extreme punishment for harassers is also arguably the exception, not the rule. Certainly, for the low-wage workers featured in this book, they felt that their claims were minimized and ignored. And from my ongoing reporting on sexual harassment in various industries, this seems to be the case for many workers in general.

Ultimately, the backlash goes beyond perceptions of inflated consequences alone. We are also grappling with shifting expectations and ideas about female agency and a woman’s ability to control sexualized behavior in and beyond the workplace. This is an incredibly individual determination, and we can’t all possibly agree.

But in the workplace, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to expect that women should feel safe doing their jobs. When a female worker takes the unusual step of raising a concern about something that makes her feel unsafe, I’d like to think that our first reaction should be to seek solutions.