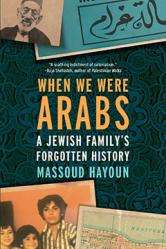

AUTHOR SPOTLIGHT: Massoud Hayoun

Earlier this year, The New Press published Massoud Hayoun’s When We Were Arabs: A Jewish Family’s Forgotten History, his moving and important debut. NPR Books says, “Hayoun weaves in his family history with the politics that shaped their lives. When We Were Arabs is a nostalgic celebration of a rich, diverse heritage” and Kirkus Reviews called the book “a remarkable tale of survival and success . . . a story worth remembering.” Below we talk with Hayoun about decolonial literature, the conflict in Palestine, and his grandmother—his collaborator and inspiration—who passed away before seeing the book completed.

Massoud Hayoun is a journalist based in Los Angeles. When We Were Arabs is his first book. For more information, please visit whenwewerearabs.com and follow him on Twitter @mhayoun.

Over the summer you were on tour with your new book, When We Were Arabs. How did people respond to the book?

I was lucky to exchange contact information with a great many (and in some cases, all) of the participants, because I had only a minute or two to speak with each of them. Many of the attendants were Arabs and Jews or some combination of the two. Many had no family relation to my ethnicity or religion but had experienced the loss of their parents or were concerned for the future of the world under so many emergent white supremacist administrations. That’s all to say that there were just too many conversations to be had. I hope there are many more events, where we can explore many of these ideas in greater depth. I learned a great deal responding to questions. I had anticipated there would be more controversial questions, but those were few and far between. For the most part, people engaged in such a way that I felt we were all—in earnest—trying to better understand each other and ourselves and our situation at this awful juncture in world history.

How can this book help us better understand the Israel-Palestine conflict right now? Can your family’s history be used to re-interpret current events in the fight for justice in Palestine?

The hope is that people will read this book and realize that this conflict has much deeper roots than the Zionist project alone—much of what transpired in 1948 was a continuation of a European colonial project in the so-called East that continues to dispossess and to disfigure. My family’s story is ours—I don’t claim to speak for anyone else’s identity and interpretation of their ethnic and cultural legacy. The very large demographic component of modern-day Israelis who are of my background do not magically become Jewish Arabs because that is how I identify. Rather, our story stands in opposition to the Arab-Jewish duality that is at once farcical and weaponized against Palestinians today. It is to say that the Arabness that is denigrated under Israel’s nation-state law and has been denigrated since the nation’s inception is my Arabness. It is to say I stand with Palestinians around the world by actively trying to destroy the false dichotomies that continue to kill and denigrate with impunity.

When did this project begin? Did you complete the journey of research and writing When We Were Arabs with a different book than you expected when you started out?

After living a fast-paced life in New York City for many years, I moved back to my childhood home in Los Angeles in 2016 to write this with my grandmother, following a great many phone conversations about Arabness and memory. Together, we shaped what this project would be, compiled what of her and her late husband’s memories were pertinent, and strategized over how to get an agent and a publisher on board. Getting a book deal is daunting; we struggled together a great deal. The beauty of that situation was that my grandmother had too much conviction in this project for self-doubt. Finally, in September 2017 (my birthday week), we got it. Three months later, she died, and I had to figure out how to stay afloat mentally while focusing on the impact of her life and death.

Can you talk about the process of writing the book with your grandmother while she was alive and also after her death?

My grandmother raised me—that was like a collaborative project. But this had been the first time we’d embarked on a journalistic and political project together. When she died, at the onset of the Trump administration and the neuroses of the society that engineered it, it became clear reflecting on our work together that my grandmother was one of precious few lucid people. She at once held great disdain and hope for humankind at the end of her life, and hoped to leave the world better.

After she died, recreating her lost world—the world of Jewish Arabs not in exile that died with her—became at once a consolation and a terror. I felt too wrapped in that world and the political theories emanating from it, at one point, and I asked my editor to speed up the whole process and get me out of there before I broke. In Arabic, we say “mektoub”—it is written or, figuratively, it’s destiny. The sense of urgency with which I wrote the latter parts of this text will hopefully impress upon people the urgency of reclaiming this world that was intended by various echelons of colonial administration to die with my grandparents.

The book addresses the tough political issues faced today concerning immigration, colonialism, culture clash, segregation, and racial/religious prejudice—all necessary to the telling of your story. Did you think this might overshadow the celebratory aspects of reclaiming your identity?

There are people who view decolonial works like this and Franz Fanon’s as forcibly heavy. I respect that. But for me, decolonialism is the opposite; thoughts of it allow me and a great many people terrified by the direction of our world to march onward with purpose. Immediately after Trump took power in November 2016, I revisited Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. In Fanon’s description of the misery of the colonial sector, I saw my family and their civilization. It is of course a great undertaking and burden to decolonize—but it is also a singular way out of immense darkness. I describe dark things in this work that happened to my family. But the fact is that the imperialists I describe had hoped I would’ve forgotten all these things by now. In the immediate [moment], the politics may seem dark, but the very essence of this book is a subversion of what is miserable and a triumph of justice, love, and family. I invite readers to rejoice with me, even if some of the immediate politics in the book are heavy. What’s more, I invite them to undertake the simultaneously sorrowful and celebratory work of decolonizing their concepts of their own ethnicities and manmade places in the world.

The way you blend memoir with political history creates a powerful effect—can you comment on that?

It is impossible for me to say whether the straight politics of this book are a backbone for my grandparents’ story or the other way around. But it becomes impossible to read one without the other. Without the politics, everything about who my grandparents were can be dismissed as weightless acts of living. And yet everything they were—down to their moments of self-loathing—was decided for them in halls of power, very far away.